The tragic toll of unquestioned traditions

Reflections on traditions, the Aggie Bonfire collapse and Brad Land's memoir, "Goat."

[I recently heard from my old classmate with some more perspective on what the new bonfire process entailed, or at least at the time circa 2016. See footnote below.]

During the early hours of November 18, 1999, a 59-foot high tower built of roughly 5,000 logs collapsed. The 2 million pound tower was being built by young college students—to be set on fire. The collapse killed 12 people and injured 27 more.

Why was this tower built? Tradition.

For 90 years, Texas A&M students had built a massive log tower to be set ablaze before the football game with the University of Texas. It symbolized “the burning desire to beat the hell out of t.u.”

Among the dead was a young man named Jerry Don Self from Arlington, Texas. I have no idea if we are related, but given the uniqueness of my last name—and the fact my extended family has long resided in the general DFW area—it is not outside the realm of possibility.

Self was among the dozen whose family had an empty chair at Thanksgiving a week later. He was described as being kind and compassionate to others and always ready to volunteer to help. He was 20 years old.

Despite the toll this particular tradition has taken, the university recently considered bringing back the bonfire as a sanctioned campus activity due to a strong push by university regents and older alumni.

As the Texas Tribune reported, noting the efforts of System Regent John Bellinger (emphasis mine):

Bellinger reached out to the families of all 12 people who died in the 1999 disaster. As of January, Bellinger had visited with six of the families, three of which gave him the OK to restart the tradition, according to committee meeting notes.

“He strongly implied, if not said, that the families who didn't agree with bringing back bonfire... they didn’t understand the spirit of the tradition and what it means to Aggies,” the committee member said.

The university ultimately decided against bringing back the bonfire.1

What was shocking to me while I was a grad student at Texas A&M was that the bonfire tradition was in fact still going on—just off campus in a non-sanctioned event. I distinctly remember a fellow classmate telling me he had stayed up late several nights that week helping to build the bonfire. Late nights with college students building massive structures out of wooden logs off campus is how people get killed. [I recently heard from my old classmate with some more perspective on what the new bonfire process entailed, or at least at the time circa 2016. See footnote below.]2

Traditions are powerful things. They bind people together as they participate in the ritual and connect them to generations from the past. I have a deep affection for Texas A&M and proudly wear my Aggie ring every day. I loved the rich history and traditions that permeated every corner of the campus. The traditions are truly what brings the community together.

But traditions can also have a deep cost. And the longer the tradition has been in place, the harder it is to question.

One of the long-standing traditions on college campuses each year is young students pledging fraternities and sororities. Like the Aggie Bonfire, the tradition has taken its share of injuries and even casualties.

But the dangers of Greek life extend beyond death and injuries. As an op-ed in Inside Higher Education argued:

The Greek system encourages excessive drinking, abusive bullying under the guise of hazing, groupthink and sexism in various forms ranging from the objectification of women to sexual assault. Thus the Greek system runs counter to the values espoused by contemporary colleges and universities.

There is no central tracking system for injuries and deaths related to college Greek life—by design—but estimates suggest there has been at least one hazing-related death each year since 1969. There were 40 hazing-related deaths between 2007 (the year I started college) and 2017 alone.

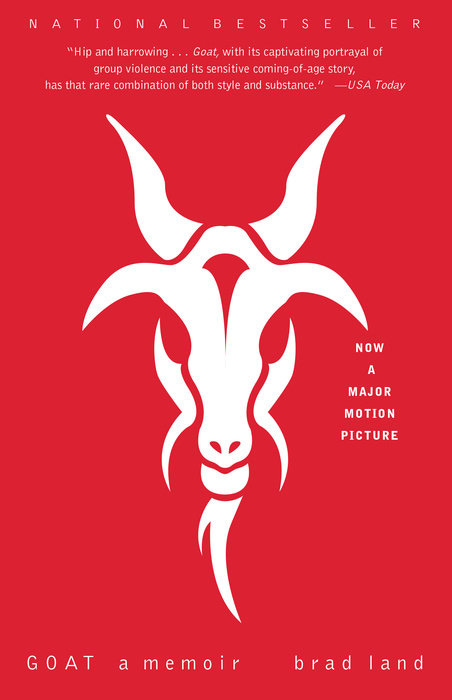

One of those deaths was a student at Clemson University in the mid-90s. The brutal hazing that took place may have been a contributing factor. One of the fraternity pledges, Brad Land, thought so. The death of his fellow pledge and the violent hazing that took place are all captured in Land’s searing memoir, “Goat.”

Goat the book

Land’s harrowing story of pledging a fraternity doesn’t begin while he was a student at Clemson University. It begins miles away in his hometown where he was kidnapped and brutally assaulted by two strangers—”The Smile” and “The Breath.”

After leaving a party, Brad is pressured to give two strangers a ride—something he almost immediately senses is unwise but feels unable to say no to. He drives for a while, growing more uncertain by the minute. And then he is attacked, shoved into the trunk and driven to an abandoned field. He is bloodied, robbed and abandoned in the middle of nowhere.

This traumatic event haunts Brad for the remainder of the book and hovers in the background of nearly every encounter that follows. Less than a year after the assault, he pledges a fraternity where physical hazing is rampant.

The driving force of this book is the physical assault Brad is trying to escape from and the bond with his younger brother, Brett, he is trying to cling to. He has not dealt with his trauma. Nor has his brother.

This is a story about many things: violence, masculinity, trauma. But this is also a story about the lengths people will go to to belong. Brad has always had a fierce bond with his brother and whether that bond can survive the pledging/hazing process is a central tension of the book. This process is supposed to bring Brad closer to his fraternity brothers and—ideally—his actual brother. But it may actually be pulling them apart.

Brett has to look on as his brother—who he knows is still struggling from his assault—is physically tormented by his fellow fraternity brothers. Brad has to endure this knowing his brother is watching it all happen.

Goat the movie

[Spoilers below for the movie and book]

Nearly a decade after Land’s memoir was published—and nearly two decades after the events took place—”Goat” became a movie starring Nick Jonas and Ben Schnetzer. Appearing briefly (but memorably) was James Franco, who also helped produce the film.

The movie largely stays true to the timeline in the book but differs in important ways—in ways I think do a disservice to the story.

The movie depicts obscene, degrading acts during the pledging process—scenes that have no resemblance to the book. Everything in the movie is an invention, likely an amalgamation of horror stories from other hazing rituals, but an invention nonetheless. This is an issue since the movie is based on a memoir, which is based on real-life events.

A major event in both the book and the movie is when a pledge suddenly dies of a heart attack and it is heavily implied that this is due to being hit in the head with a piece of fruit during a pledging event. The loose connection between being hit with a piece of fruit and dying of a heart attack doesn’t make the connection between the hazing and the death clear.

In the book, the pledge is callously kept out of the fraternity after he endures several torturous weeks of hazing. It’s clear that belonging in the fraternity is central to this pledge’s identity. The cruel way he is cast out seems like a much likelier scenario that would lead to a heart attack the day after being denied entry to the fraternity.

Since a death is involved, I think straying too far from the events described in the book is an issue, especially when the link between the hazing and the death becomes even murkier.

In the movie, the death and the following investigation lead to the fraternity being disbanded. The pledges who endured all this torture are faced with the reality that it is all for nothing. The members are confronted with real consequences for their actions. Brad, who stayed with the pledging process until the very end, has to confront these questions, too.

This is not how events play out in the book. There’s an investigation, but little comes of it. The fraternity continues on. Justice is not served.

This alternate ending also removes a lot of agency for Brad. In the book, Brad depledges after reaching a breaking point. As someone who depledged a fraternity/social club, I think that’s a pivotal decision and removing it makes Brad more of a passive bystander in what’s happening to him.

The book and the movie were an emotional experience for me as it brought back memories of my own experience pledging and then depledging a social club/fraternity.

In the coming weeks, I plan to share my own experience with pledging that took place in the fall of 2008 while attending a Christian university. The hazing and physical activities—while far from what was described in “Goat”—were still shocking to me. I’ve been waiting to share this for a long time.

My Top 10 Books of 2024

I don’t listen to Spotify, robbing me of the yearly Spotify Wrapped many of my peers enjoy. I’m not on Letterboxd enough to get end-of-year personal stats based on my reviews and viewing habits. I have never watched yet alone heard of any of the best films of 2024, as chosen by The Economist

Why good people are divided by politics and religion

When Jonathan Haidt published “The Righteous Mind” in 2012, it seemed America was uniquely divided politically. I remember watching a debate between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney and hearing one pundit say it was one of the most contentious presidential debates he had ever seen. Simpler…

The president of Texas A&M, General (Ret.) Mark A. Welsh III, was previously the dean of the Bush School of Government, where I went to grad school, and by all accounts is a very wise and decent person.

My former classmate at Texas A&M reached out with a kind message to add a bit more context: “the Bonfire culture that I encountered was the direct opposite of the work safety-irreligious entity that pre-collapse Bonfire was. We had drastically revamped the system of how we put logs together and secured the overall structure, with consistent and recurrent input from licensed professional engineers. People pulled long shifts, but in my 4+ years of participating and observing, the risks were mitigated effectively and when an unsafe practice was observed, the response was immediate and definite.

I have worked in a professional capacity in multiple industries since then in projects on a similar or greater scale, and still look back on that as an impressive demonstration of the community determination to eliminate the factors that led to the Collapse. Perhaps if you went to a Stack shift this fall you could confirm or deny- I haven't been back in close to a decade so cannot definitively state that it is still so.

What I would finally offer that made it an enterprise of value, a thing that was worth continuing, was that it provided a space for people learning how to be adults (adults that would soon play real roles in real industries with real risk on real work projects) to also learn how to manage and participate in group projects outside of the purely academic context, with tangible physical products, with the resultant irreplacable feel of a job well done, and admittedly with tangible physical risks (swing an axe at a tree, pick something heavy up). I know I specifically carried many aspects of my experience working on it in a productive way into my subsequent career, and it helped.

There was hazing inarguably historically tied in with it, and people during my era and immediately prior shut that down. I would be shocked if that attitude had not continued. My experience with it was that it gave a multiethnic crowd of people with a broad swath of sexualities an unusually inclusive experience of working hard physically and making fellow friends who worked hard in an environment divorced from whatever was going on with academics or personal life at the moment.