Why good people are divided by politics and religion

Reflections on Jonathan Haidt's "The Righteous Mind"

When Jonathan Haidt published “The Righteous Mind” in 2012, it seemed America was uniquely divided politically. I remember watching a debate between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney and hearing one pundit say it was one of the most contentious presidential debates he had ever seen. Simpler times. In hindsight, we all know things were about to get much, much worse.

But the insights Haidt brings with this book are just as—if not more—important to understanding what divides us across politics and religion now as they were in 2012. Because the reasons we’re divided in 2024 are the same reasons people have been divided for millennia. It is part of human nature to divide ourselves into in groups and out groups and the more we understand those basic human impulses, the more we might be able to turn the page on this current age of deep polarization.

Intuitions Come First, Strategic Reasoning Second

When I was in high school, the file-sharing service LimeWire was a popular way to (illegally) download music and other media for free. It was obviously unethical to download copyrighted material without paying for it, but many of us had convinced ourselves otherwise because…well, because we wanted to be convinced otherwise.

When my cousin helped me download LimeWire, she explained it was different from Napster (which had been shut down) because the files were being shared peer-to-peer so it was just like sharing a burned CD among friends. That’s all I needed to set my ethical concerns aside. I wanted this to be a moral activity and just needed a rationale to justify my behavior.

Not even compelling arguments from the Motion Picture Association could help me see the light. You wouldn’t steal a car (which costs tens of thousands of dollars and would require you to hijack a car in broad daylight) so why would you steal a movie (which costs about $15 and you can download from the comfort of your own home)?

Everyone would like to believe their moral decisions are the product of purely rational thought. Our minds clearly see right and wrong and come to conclusions based on logic. But that is not the case. As Haidt notes:

If you think that moral reasoning is something we do to figure out the truth, you’ll be constantly frustrated by how foolish, biased, and illogical people become when they disagree with you. But if you think about moral reasoning as a skill humans evolved to further our social agendas—to justify our own actions and to defend the teams we belong to—then things will make a lot more sense.

One of the central metaphors of the book is the rider and the elephant. The rider is your rational, conscious mind and the elephant is “the automatic processes, the 99% of what’s going on in your mind that you’re not aware of.” The rider sits on top of the elephant and can gently guide the animal in a certain direction. But if the elephant doesn’t want to move or wants to go in a different direction, then the rider is literally along for the ride.

People spend a lot of time trying to convince the rider with facts, figures and logic but if the elephant doesn’t want to move it won’t. If you try to understand someone’s emotions, the fears and underlying motives—the elephant—you may find more success at winning people over to your side, or at least helping them understand your position.

There’s More to Morality than Harm and Fairness

Haidt’s research led him to identify five moral foundations—care, fairness, loyalty, authority and sanctity—and later a sixth, liberty. After collecting surveys from more than 130,000 people on the original five moral foundations, a clear pattern emerged: “Liberals value Care and Fairness far more than the other three foundations; conservatives endorse all five foundations more or less equally.”

It’s not that conservatives don’t value Care and Fairness, it’s that they don’t value those foundations as highly as liberals while also valuing other foundations. This is an important insight for anyone, especially those who seek to persuade others.

Speaking only about harm can be effective when preaching to the liberal choir or making fundraising appeals, which research shows are most effective when people are angry. But if you want to actually persuade people, this may not be the best tactic.

Last year, the Human Rights Campaign announced: “We have officially declared a state of emergency for LGBTQ+ people in the United States for the first time.” For the first time in the HRC’s more than four-decade history. To anyone who lived during the Lavender Scare, the AIDS epidemic, before anti-sodomy laws were struck down, before marriage equality became the law of the land, or before the Bostock decision banned workplace discrimination based on sexual orientation—this declaration might come off as more than a bit alarmist.

This heightened rhetoric might help galvanize people on the left but is less effective at convincing those on the right or in the middle.

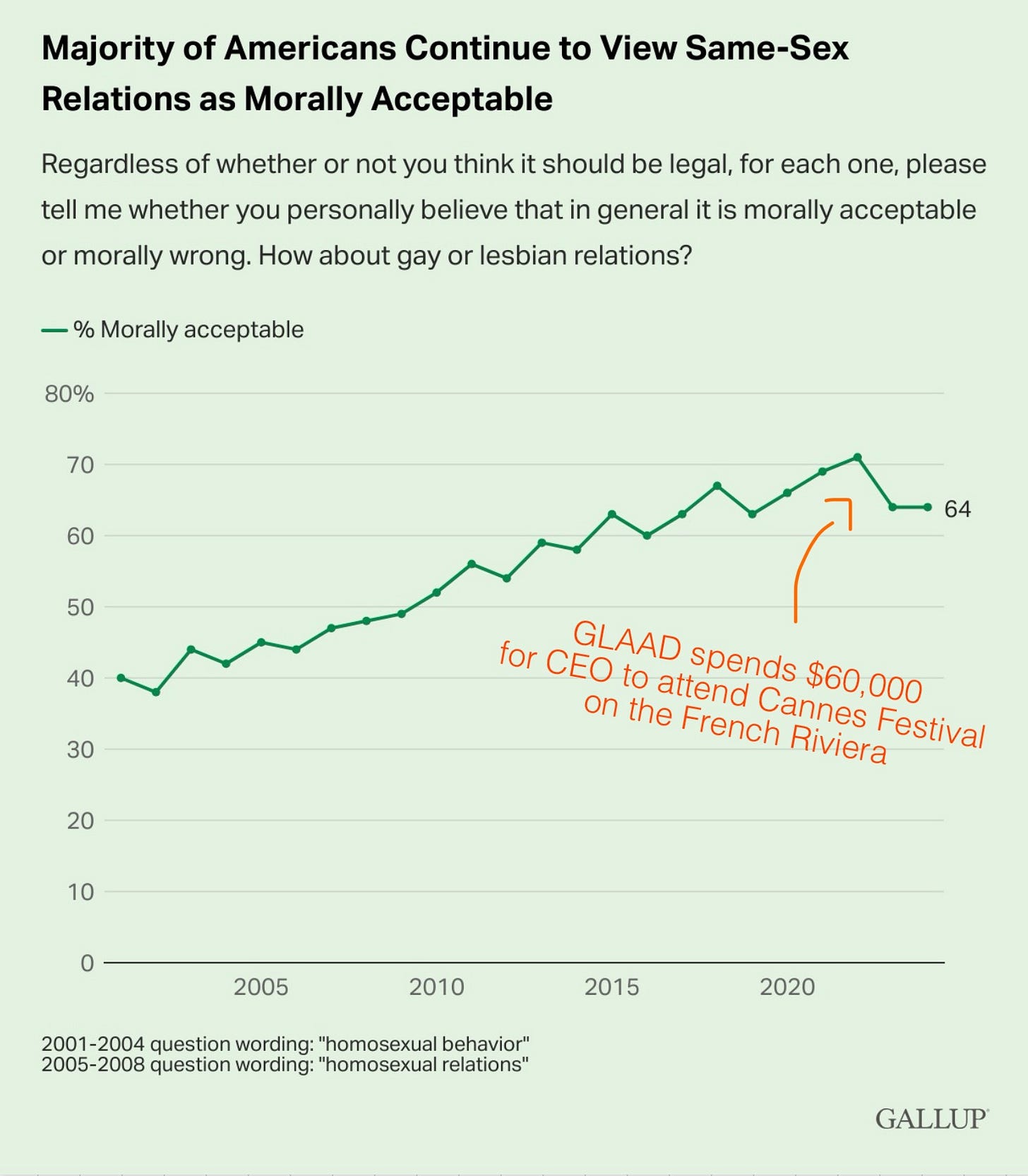

Recently, GLAAD came under fire when The New York Times revealed lavish spending by its CEO. The report detailed 30 first-class flights in 18 months, a “work trip” to the Cannes Film Festival, nights at the Waldorf Astoria, and a $25,000 annual stipend for the CEO to rent a summer home in Provincetown, Massachusetts.

Clearly, the group is flush with cash due to a marked increase in fundraising. Meanwhile, support for same-sex marriage is starting to slip.

If you are primarily concerned with fundraising appeals to other like-minded liberals, you emphasize the Care foundation. If you want actually to persuade those across the political spectrum, you emphasize all five foundations.

This is the argument made by Matthew Vines, an activist and author whose organization, The Reformation Project, seeks to advance LGBTQ inclusion in the church. He noted that in arguments for same-sex marriage, liberals can sometimes fall into the trap of overemphasizing Care/Harm appeals while ignoring the appeals more conservative Christians might also be concerned with. The Reformation Project does an excellent job of addressing conservatives’ concerns about Authority by making arguments within the Christian tradition; about sanctity by emphasizing lifelong, monogamous relationships; about loyalty by sharing stories of gay Christians who want to remain in their faith tradition.

The goal is to reach people who may be open or “in process” understand their concerns and try to meet them where they are. This takes work. This can be frustrating. This won’t always yield positive results. But this is much more effective at changing people’s minds than

Morality Binds and Blinds

Humans are social creatures. We are oftentimes selfish but can also be groupish. Morality can help individuals transcend their own self interest in the service of the group, uniting them around shared beliefs, values and goals. While this leads to increased cooperation within the group, it can also blind them to other perspectives from outside the group.

When I was in college, I pledged (and then depledged) a social club, which was the Christian college equivalent of a fraternity. During the week I suffered through pledging, every activity was an exercise in building group cohesion while making clear distinctions with those in the out groups—typically other social clubs.

Nearly everyone who wanted to, and survived pledging, got into these clubs. The actual stakes could not have been lower. People weren’t competing for lucrative jobs, huge cash prizes or any kind of material benefit other than belonging to a group. And yet—friendships were often torn apart, people from other clubs became undesirables, and the fierce desire to belong led pledges to do truly stupid things like jump through fiery hoops at an intramural game.1

When I depledged and wrote an op-ed for the student paper about the problems I saw with the pledging process, I quickly went from being an insider to an outsider. (There was a rebuttal from the “secretary emeritus.”) People who once eagerly recruited me to be part of their group wouldn’t make eye contact with me if they saw me.

People belong in groups, and that sense of belonging can drive how they see themselves and form their own beliefs. And in plenty of cases, it can lead to terrible behavior.

Even in the best of circumstances, getting people to go against what is seen as “the party line” can be a gargantuan task. As David French, New York Times columnist and former writer for The Atlantic, puts it:

When you argue politics with a person, you’re often not simply asking them to change their mind, you’re often asking them to change their identity. You’re asking them to possibly lose their community and forfeit friendships. You’re sometimes asking them to shift the very sense of purpose that has defined their life.

Final Thoughts

A recent study on private opinion in America suggests most people feel enormous pressure to hold the “right” beliefs. Certain groups have a large gap between what they say publicly and what the believe privately. A large driver of this is the social pressure they feel to remain in good standing with their particular tribe.

Among the study’s findings:

A majority of Americans (58%) believe most people cannot share their honest opinions about sensitive topics in society today. And they are not wrong: Not only do 61% of Americans admit to self-silencing, private opinion methods reveal that every single demographic group is misrepresenting their true opinions on multiple sensitive issues.

Across demographic groups, college graduates and political independents self-silence the most often, with double-digit gaps between public and private opinion on 37 of 64 issues.

People who self-silence have a social trust score that is 22-points lower than people who do not (30% and 52%, respectively).

Venturing outside your bubble is not easy. It takes conscious effort. As many people are sensing, it can also jeopardize relationships, which only leads to more polarization, which leads to less dialog, which leads to more polarization. Political extremes have made constructive dialog feel impossible. But if we were to start having those conversations, we might be surprised at what we learn. That same aforementioned study also had the following findings:

For two-thirds of the sensitive issues studied (43 of 64), ranging from abortion rights and school choice to legal immigration and voter ID requirements, 90% of demographic groups are privately on the same side of the issues.

Haidt has provided a helpful tool for understanding those with different beliefs and I believe his closing thoughts in the book also provide a helpful way forward:

If you want to understand another group, follow the sacredness. As a first step, think about the six moral foundations, and try to figure out which one or two are carrying the most weight in a particular controversy. And if you really want to open your mind, open your heart first. If you can have at least one friendly interaction with a member of the “other” group, you’ll find it far easier to listen to what they’re saying, and maybe even see a controversial issue in a new light.

(NOTE: If you think I am being naive about the state of political rhetoric and polarization in the country, especially the extreme rhetoric of figures like Donald Trump, know that I plan on writing about that in a future post. This is part one in a series.)

Additional Reading

This was among the milder things I witnessed during pledging. What happened off campus was truly terrible. I’m contemplating writing about those experiences as some point.

I read Jonathan Haidts book a few years ago and still cite the rider and elephant example today with my friends that have different political and religious stances from myself. It was an incredibly insightful read and helped me communicate more effectively and hold more empathy for others (while also maintaining an open mind and heart myself whenever I would listen to them and recognize my own elephant getting triggered, lol).

Great article, Ryan and love the modern examples you included. As you mentioned, the greater challenge these days is reaching across the aisle to others "outside of our group". Nowadays we can easily tune out news stations that don't align with our political views or simply "unfollow" others on social media if we disagree with them. The resulting effect creates echo chambers that only further perpetuate tribalism and group-think behavior of, "I'm right and you're wrong". A great book that compliments Haidt's is Justin Lee's, "Talking Across the Divide". In it, he further explores the modern challenges of why it's so hard to reach our neighbors across the political/religious aisles and provides meaningful ways to engage in healthier dialogue. I particularly recommend people read both books right before Thanksgiving time as we all know those family gatherings are the true test to practice what we've learned 😂

One of my fave books! Great summary 🙌