The reckoning and wreckage of a progressive evangelical church

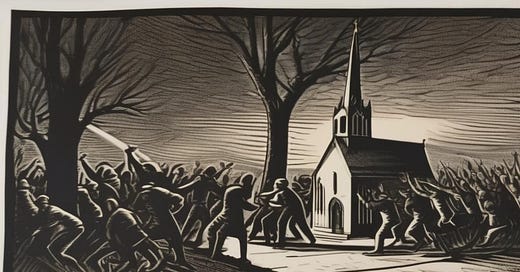

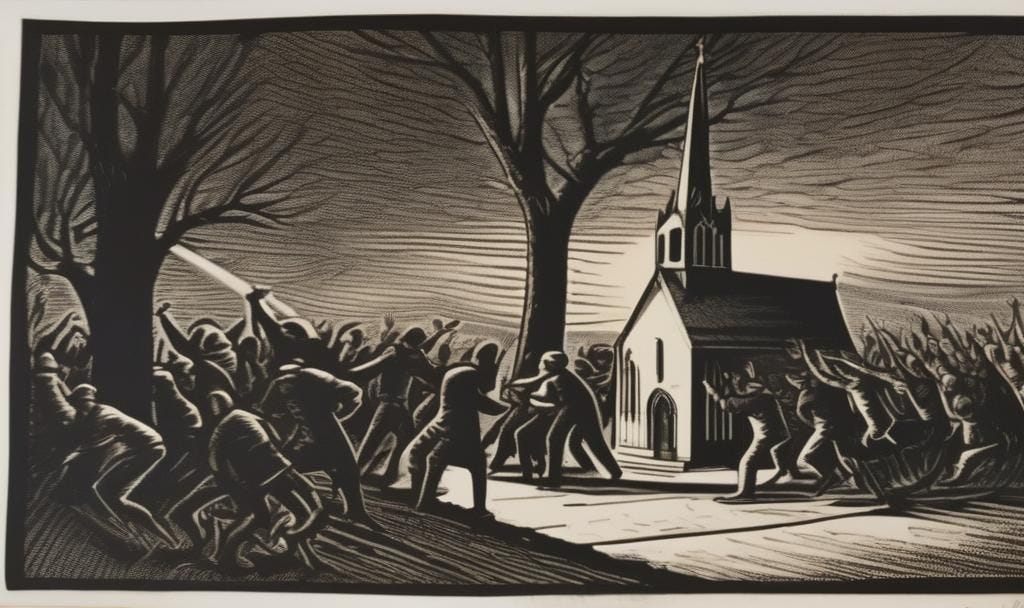

Eliza Griswold's "Circle of Hope" documents the implosion of a once thriving church torn apart by political infighting

[NOTE: Hours after publishing, I received a text from a board member at one of the churches mentioned in the post. See footnotes for my response.]

To some, it seemed that only those who held the right views were welcome to participate; others were shut out as backward. Asking questions had become synonymous with dissent, and dissent, by definition, was anti-change and anti-progress, since it slowed pushing forward toward righteousness.

When Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Eliza Griswold set out to write the story of Circle of Hope, she thought she would be writing about the success of a growing evangelical progressive church. She had been shadowing author, activist and speaker Shane Claiborne in his neighborhood in Philadelphia when she came across a group of people so intriguing she had to learn more.

Over the next few years—through COVID, racial reckonings, power struggles and rapid cultural changes—she attended hours of zoom calls, sermons and anti-racism trainings. You’ve heard the Gospel According to Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. This is the story according to Rachel, Julie, Ben and Jonny—the four lead pastors trying to navigate a period of deep dysfunction and change.1

What she documents is harrowing—in every sense of the term.

Ultimately, the founding pastors, their son and most members of their family were cast out of the church. “There was no hint of scandal, no rumor of sexual or financial abuse…. Yet Circle of Hope seemed to be turning against them.” Various reasons were given. One camp believed the founders had been “sowing seeds of discord.” The family, as one member put it, felt they “were crucified on the cross of wokeness.”

What began as a story about a quirky but committed group of Jesus followers became a post-mortem about the collapse of a beloved community. While the details of the story are unique to Circle of Hope, the overarching story of how disagreements tear communities apart is universal. As David French noted in his review for The New York Times:

I thought I was going to be reading a deeply researched story about a unique Philadelphia church. Instead, I found myself reading a story that countless millions of Americans might instantly relate to—about how political disagreements can fracture the closest friendships and break the best institutions.

The narcissism of small differences

In multiple podcast interviews, Griswold has mentioned a common refrain from previous members who read the book was, “I didn’t realize how close we were.” The gulf between individuals—especially among the four lead pastors—seemed so wide in the moment but with some time and perspective, the differences seem much smaller.

It wasn’t that one camp wanted to engage in anti-racism work and the other camp was opposed. There was disagreement on how exactly that anti-racism work should be carried out.

An early inflection point was after the police shooting of an unarmed black man in Philadelphia. There was no disagreement that this was an appalling loss of life, that police violence was a problem, that race was a factor and that the church should speak out.

What they disagreed over was the wording of the official statement from the church and whether it should include calling for the dismantling of the Fraternal Order of the Police. Some members wanted time to consider the wording, others saw any hesitation as a problem with whiteness.2

This was a common theme: the members and leaders were generally aligned, but unless the church responded in a specific way, for some, it was as if they were diametrically opposed.

That rift only grew over time.

A rapid cultural shift from Anabaptism to aggression

In their efforts to progress past toxic practices, the younger members and pastors were often inclined to throw out old traditions—not just harmful ones. Over the decades, the church had developed more than 100 proverbs to guide their shared life together. In early 2022, they cast those aside in favor of six new proverbs, all centered around racism, ableism and LGBT inclusion.

The decision to become fully LGBT-affirming didn’t just have theological repercussions but material ones, too. Becoming affirming could cause the church to be cast out of the Brethren in Christ denomination, which could lay immediate claim to the church’s buildings and assets—more than $3 million.

The decision came almost overnight in one of the most heavy-handed ways possible. There would be no open discussion. Anyone opposed would be contacted by their pastor to discuss the topic. While some members believed that “doing theology” required wrestling with Scripture as a group, those days were over.

When two dissenters voiced their concerns over not just the policy but the lack of dialogue, they were shut down. They decided to leave the church.

“When homophobic people leave your church it’s a good thing,” one of the pastors, Jonny, tweeted the following day, which alarmed many members. A growing unease was forming as people began to feel if they openly disagreed with Jonny, they would be called racist or homophobic on social media, which might cost them their jobs.

For decades, Circle of Hope had viewed theology as a collaborative process, not a top-down dictate. But with topics like LGBT inclusion and anti-racism, the tone was becoming more rigid, or in the words of Jonny, “Move with us or make a choice to leave.” This was especially jarring to longtime members considering the church had been firmly rooted in the anabaptist tradition of peacemaking and pacifism. Hardball tactics had previously been anathema to the church’s culture.

Later that year, Circle of Hope threw all of their proverbs out. They were making a clean break with the past.

When “love” becomes problematic

There are some absolutely wild passages in this book. Consider the following:

“[Rachel] didn’t know how to talk anymore; even the word “love” had become contentious. For Rachel, love was the most basic building block of their community; for Julie and Jonny and many others, “love” had become code for accommodationist politics.”

If you are a leader of a church and the word “love” has become problematic, you have truly lost the plot. When Jesus is asked “What is the greatest commandment?” in Matthew 22:36-40, he responds:

Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind. This is the first and greatest commandment. And the second is like it: ‘Love your neighbor as yourself.’ All the Law and the Prophets hang on these two commandments.

This absence of love appeared to contribute to the seeming indifference toward the people who were leaving:

Yet [Pastors] Julie and Jonny didn’t seem to mind that people were fleeing from Circle of Hope. “This bleeding out is a bleeding out of white people,” Julie told Rachel at the first pastors’ meeting following the debacle at Marlton Pike.”

People are invested in their churches. They raise their children there. They grow deep communities there. Many build their lives around their church. So it is natural when there is constant tension and longtime members are leaving in droves, people become anxious and turn to their pastors for comfort. And yet when people turned to Julie, one of the white pastors at Circle of Hope, they were met with coldness:

Julie wasn’t indulging their grievances or convincing anyone to stay. She was pointing out, time and again, how their sense of injury was rooted in their whiteness. She took no pleasure in leaving old friends behind; it ran counter to her every fiber not to offer solace, but she held the line against old habits, no matter how cold and distant it felt.

The lack of grace was rampant at Circle of Hope. In one of the small groups, after a black woman, Bethany, was struggling to do a good Trump impression, an older white man, Tim, made a bad joke that “you have to get the Black out of your voice.” In his telling, he offered an apology right away when he realized he’d been offensive. Bethany called him out within the group. When Tim wrote a letter of apology to be delivered by one of the pastors, Bethany refused it.

Months after the incident, Bethany wrote about what happened on Facebook. When Tim saw the post, he questioned why Bethany did not talk to him in private instead of humiliating him in a public forum. He also said he assumed they were no longer welcome. Bethany told him to “grow up in Christ” and never contact her again, and blocked him on social media. Tim reached out to a pastor, Julie, but she was no help. She stood by Bethany. Tim and his wife were essentially shunned from the church. For a joke.

Bethany would go on to become akin to a lead pastor due to her anti-racism work (she is the only non-pastor with her own separate chapter). She would have all the authority of a pastor, a fraction of the responsibility and none of the accountability.3

When commitment to a cause competes with a commitment to Christ

There were so many factors that led to the collapse of Circle of Hope: COVID restrictions leading to people meeting over zoom instead of in person, the overbearing founding pastors, the toxic behavior of the two male lead pastors. But arguably the biggest issue was replacing Christianity with an activist ideology. Love had become problematic. Grace and forgiveness were foreign concepts. Working through disagreements was replaced with “Move with us or make a choice to leave.”

There’s plenty to be alarmed about on the political and theological right these days. The alarming rise of Christian Nationalism. The unholy alliance of Republican politics and Christianity. Many conservative churches have shoved Jesus aside to make room for their politics or conservative ideology. But Christianity can be pushed aside for progressive ideology as well.

I saw this at a church I used to attend in Austin. The dominant word this church uses to describe itself is “progressive.” The short description on its social media is “An inclusive, progressive faith community.” It’s a word used on the website to describe the lead pastor (“progressive by nature”) and the first adjective used to describe it on the “About Us” page. Words you won’t find on that page: “Jesus,” “God” or “Christian.”

Some variation of LGBTQ+ is found six times on the “About Us” page alone. It is perhaps this elevation of progressivism over Christianity that led this church to host a drag show back in June. Because of the laws in Texas, the show, “Drag Me to Church” was labelled 18+, which is an odd thing to market inside a church.4 Because of the decision to host a drag show, the church lost members.

I left that church about a year ago. Almost everyone from my friend group of about 10 people left before I did. That church is struggling financially. The founding pastor and children’s pastor have left. Several LGBT people like myself also left that church and many found our way to another church in the same zip code that was affirming but with more emphasis on Christianity.5

That church’s “About Us” page is very different. “Christian” is mentioned twice, “Jesus” and “God” are both mentioned nine times, “The Bible” is mentioned twice. A word nowhere on the page: “progressive.” When my current church was approached about co-hosting the drag show, they declined. My current church added a second service earlier this year and many more join each week.

The church that has kept Jesus, God and Christianity at the center of its identity is thriving. The “progressive faith community” that has metaphorically draped the pride flag over the cross is imploding. I don’t think this is a coincidence.

Final Thoughts

Like many people at Circle of Hope and across the country, during the pandemic I also started to re-evaluate my relationship to the church I was a part of for years. I was often angry when I logged on to weekly zoom calls. I was angry that we weren’t meeting in person, even outdoors. I was angry that my life group and church weren’t motivated to have discussions about homophobia. (Not more discussions or better discussions, just any discussion period.)

But these people had also been my community for the past few years. We had celebrated birthdays together, movie nights and Halloween parties. The group leader had driven across town to deliver some cookies during the pandemic. Once she realized how she hadn’t shown up for me in the past as a gay person, she signed up for a virtual conference on the topic of LGBT people in the church, not a small act of love.

The progressive church I mentioned above was where I met some of my closest friends. There are two couples there that regularly welcome people into their homes for a shared meal. These communities have been the lifeblood of my time in Austin.

The same was true at Circle of Hope. These people had been in each other’s weddings, celebrated births, attended funerals and helped each other move. The fraying of the church meant lifelong friendships and communities were being torn apart. The story of Circle of Hope doesn’t have heroes or villains, just complicated, messy people trying to do what they believe is best and often going about it in counterproductive ways.

Church is hard. You’re often in deep community with (ideally) people from a variety of backgrounds and experiences. What bonds you is a shared faith, one of the most personal and deeply held experiences one can have. It’s natural that disagreements will arise. And because the bonds are deep and the beliefs are sincerely held, disagreements can be painful. But church is also worth it. As the writer Jeff Chu notes:

Isn’t this the human story? Good intentions never guarantee perfect results. Beauty and courage almost always exist alongside ugliness and cowardice. Hope always carries the possibility of disappointment, even devastation.

Yet still we try—to do right, to live in community, to seek the good that is beyond the reach of any one individual.

“Circle of Hope” is a fascinating read, but also a hard look at why friendships and institutions get torn apart. Perhaps by learning the lessons this community wasn’t able to see at the time, other communities can avoid the same demise.

Why good people are divided by politics and religion

When Jonathan Haidt published “The Righteous Mind” in 2012, it seemed America was uniquely divided politically. I remember watching a debate between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney and hearing one pundit say it was one of the most contentious presidential debates he had ever seen. Simpler…

Scout Finch can't go home again

I can only answer the question ‘What am I to do?’ if I can answer the prior question ‘Of what story do I find myself a part?’

Griswold has said that while it wasn’t stated in the book, by dividing the book into parts and dedicating each chapter to one of the four pastors, she was trying to play off the four gospels.

Later in the book, when the pastors come out of anti-racism training and want to move quickly, they are warned, “When we move with urgency, people of color get hurt.”

To Bethany’s slight credit, in an episode of her podcast featuring Griswold, she did say she felt “a little cringey” about the incident and that she might handle it differently in the future. Her co-host immediately jumps in to defend Bethany and say she was right in the moment. After reading the book, this interaction feels like a microcosm of what might have been the culture of Circle of Hope, where even a moment of introspection is shooed away.

If a progressive church wants to encourage members to go somewhere else to a drag show, fine, it just seems inappropriate to take place within the church.

Hours after I published this post, I got a text message from a board member at the church I used to attend. The board member said “To imply that we aren’t a Jesus centered church because it isn’t mentioned on the website is wrong and misleading.” I don’t think stating what is on an organization’s website is wrong and misleading. I am basing my judgment on the website and my two years of attending that church. I am far from the only one who feels this way. Just yesterday, I was talking to a couple that used to attend that church and they noted it felt like the sermons were only deconstructing faith without any reconstruction.

The board member also stated “our children’s minister did not leave for financial reasons, and we replaced [founding pastor] with another full-time pastor. We also replaced [children’s minister] almost immediately.” That seems misleading. No new people were hired (you can see this on the website). Additional duties were just shifted to existing staff. For financial reasons.

The remainder of that section is facts. The text on the website is a fact. The 10 friends who have left the church is a fact. The financial struggles are a fact. The multiple LGBT people who have left the church is a fact. I stand by the remainder of the text.

The board member also took issue with comparing/contrasting the two churches. I felt these two churches—with which I have direct experience—represent two paths an affirming, left-leaning church can go. I want those who are new to the idea of an affirming church to understand that affirming does not have to mean “progressive.” I reject the idea that part of being affirming means hosting drag shows. I also want people to know that LGBT Christians care deeply about Jesus, God and the Bible and many will flock to a Jesus-centered church over a progressive faith community that makes LGBT affirmation the core of its identity.

Ooof! 'Circle of Hope' was a slow motion, high impact gut punch for me! I felt both engrossed in Griswold's storytelling... while also feeling sick to my stomach the entire duration. It's for the very same reasons you gave that my partner and I drive an hour each way every Sunday to attend a church in a different city - one that fully includes us as a gay couple, but doesn't at all resemble a 'Gay Pride Church.' It’s nice to know I’m not alone in how I felt reading this book! 😁

I dated someone in 2021–22 whose father was a COH member. He hosted Bible studies at his apartment. I have met Pastor Rachel, who was personable and friendly. It’s amazing, and sad, to read about this drama. “In essentials, unity; in non-essentials, unity; in no things, charity.”