What if you're a sociopath?

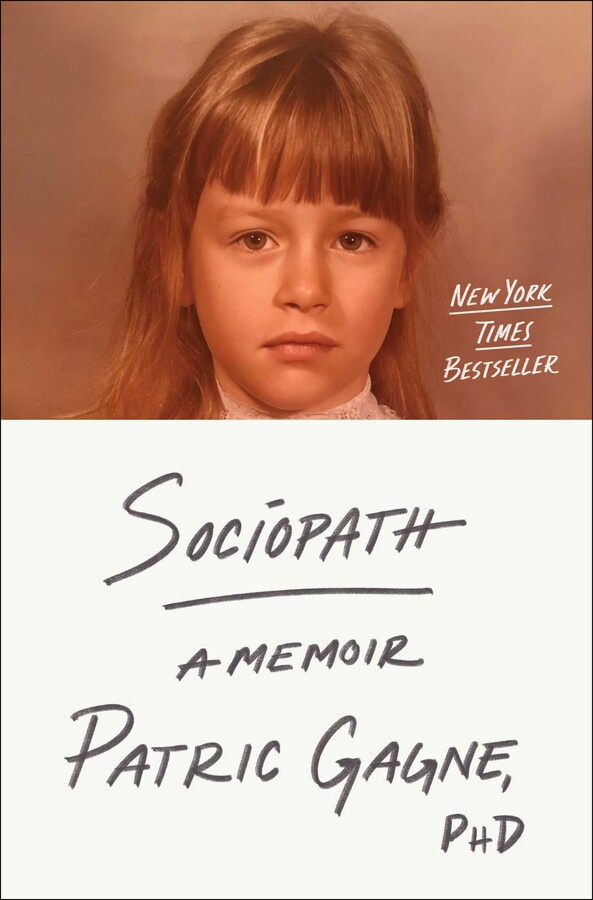

Patric Gagne's memoir, "Sociopath," gives insights into the life and mind of those who struggle with empathy and remorse.

There are an estimated 15 million sociopaths living in America. One of them is Patric Gagne. She is a passionate mother and wife, an engaging therapist and by all appearances someone you would want to be friends with. But outward appearances can be deceiving.

As Gagne writes in the opening chapter:

I’m a liar. I’m a thief. I’m emotionally shallow. I’m mostly immune to remorse and guilt. I’m highly manipulative. I don’t care what other people think. I’m not interested in morals. I’m not interested, period. Rules do not factor into my decision-making. I’m capable of almost anything.

How she navigates the world is the topic of Gagne’s memoir, “Sociopath.” Witty, smart and vulnerable, Gagne shares her unique journey while weaving in valuable research (she has a PhD in clinical psychology). She has been able to create a stable, healthy life, but it has been a long road since a childhood where she first realizes she experiences the world differently than her peers.

Under pressure

One of the great gifts of the memoir is Gagne’s ability to articulate what goes on in the mind of a sociopath. Growing up, the stress that comes with not feeling an emotion—yet sensing you are supposed to be feeling strong emotions—would create a building sense of pressure for Gagne:

It was like mercury slowly rising in an old fashioned thermometer. At first it was barely noticeable, just a blip on my otherwise peaceful cognitive radar. But over time it would get stronger. The quickest way to relieve the pressure was to do something undeniably wrong, something I knew would absolutely make anyone else feel one of the emotions I couldn’t.

So that’s what she does. As a child, she steals backpacks, lockets and toys. She sneaks into houses. As she grows older, she steals cars and breaks into homes, sometimes while people are in them. Stalking is a common pastime. All of this is done to keep the pressure at bay. Because if the pressure grows too strong, she might do something completely reckless.

Like when she stabbed a girl in the head with a pencil.

There are many moments in the book when Gagne senses she is right on the edge of doing something reckless. Such as the time she snuck into the backyard of a woman (who had been trying to blackmail her father) and is moments from attacking her when the woman’s child walks into the backyard.

Learning to hide

Gagne’s mother always encourages her to “tell the truth,” but Gagne slowly learns that telling the truth can make people pull away from her. When she admits to not feeling certain emotions or reveals what’s going on inside her head, people often react in shock. They treat her differently. They start to avoid her.

Conversely, when she pretends to express emotions she doesn’t truly feel, people are more comfortable around her. This is a revelation. When she learns to form the facial expressions one would expect in a social situation, she is able to create bonds with other people and develop relationships.

Gagne begins to study her peers to figure out how someone “normal” would react in certain social settings. She attends fraternity parties less for socializing and more to watch her peers interact and take mental notes:

College parties offered some of the best people-watching in town. These gatherings were a virtual master class in social interaction and featured every type of behavorial observation possible. Attending them was like getting a jolt of feeling by omsosis.

This “feeling by osmosis” also becomes a common coping mechanism. Being around those who are experiencing strong emotions helps her feel some sense of that emotion. This behavior led to one of the many moments in the book where I laughed out loud—not because it was necessarily funny, but because what Gagne wrote was so unexpected. Gagne explains that she regularly attends church on weekends, but not for the reasons most people go:

“Which one are you going to? I’d love to go with you, if you didn’t mind.”

I rocked my head from side to side. “I mean, I wouldn’t mind. But I don’t think you’d like it.” I hesitated. “They aren’t normal church services.

“What do you mean?”

“They’re funerals.”

Navigating life as a sociopath

It was while she was in prison as a little girl—as a visitor, not an inmate—that Gagne first heard the word, “sociopath.” She was visiting her uncle, who was a prison guard, and a coworker shared his belief that 80% of the inmates were sociopaths. The idea that prison is the likely fate for a sociopath haunts Gagne well into adulthood.

She quickly realizes there are few resources to turn to. Sociopaths are not a sympathetic population, nor are they well understood. Depictions of sociopaths in pop culture are almost always evil people seeking to harm others.1

As an adult, during a group discussion with her fellow therapists, one therapist announces, “I’d rather my kid have cancer than be a sociopath.” The room nods in agreement.

A healthy, long-term relationship helps ground Gagne. But soon the old demons return. With the help of a therapist, she learns better coping mechanisms and delves into the root causes of her sociopathy. Today, Gagne is married, has two children, and is a successful therapist. But the journey to get there was not easy.

The sociopath next door

When I was in first grade, a boy moved next door. We’ll call him Sam. He was a few years older than I was, but being new to the neighborhood he came over to play one day. While we were in the backyard during his first visit—without warning or provocation—he started hitting me in the back with a stick. All I remember is that one minute we were playing and the next minute I was on the ground as this kid older than I was started wailing on me. My mom saw this from the kitchen window and immediately came outside to tell him to stop and to go home.

The next day, Sam knocked on our door.

“Can Ryan come out to play?” he asked, innocently.

“No, Ryan is not playing with you. I saw you hit him,” my mom replied sternly.

“No, I didn’t,” Sam responded without any trace of guilt or shame.

This anti-social behavior did not endear him to the other neighborhood kids. I remember waiting for the school bus as Sam stood on one side of the street and the rest of the kids stood on the other—throwing rocks at Sam.

Although I didn’t join the rock throwing, I didn’t have compassion for Sam. But if Sam was in fact a sociopath, and remorse and empathy were inherently difficult for him to experience, it does change how I feel about him as an adult.

Sam had a harder time navigating the world. The emotions that came naturally to most people, might not have come easy to Sam. I don’t know what a good response to him would’ve been (keeping my distance from him as a first grader was still the right call) but literally stoning him wasn’t the answer.

There is a growing understanding that some individuals are genetically or biologically predisposed to criminality. Does that change our approach to criminal justice? If there are 15 million sociopaths in the United States, shouldn’t we be doing more to help? If sociopathy is so stigmatized that people learn to hide their lack of emotion rather than get honest about their experiences and seek help, isn’t that just excacerbating the problem?

Again, I don’t have good answers to these questions, but I do think they are worth asking. And hopefully Gagne’s memoir will help more people develop empathy for those who struggle to experience empathy themselves.

More resources

Armchair Expert with Dax Shepard episode with Patric Gagne

Gagne’s New York Times op-ed about her relationship with her husband: “He Married a Sociopath: Me.”

New York Times interview with Gagne: “What It’s Like to Be a Sociopath.”

My Top 10 Books of 2024

I don’t listen to Spotify, robbing me of the yearly Spotify Wrapped many of my peers enjoy. I’m not on Letterboxd enough to get end-of-year personal stats based on my reviews and viewing habits. I have never watched yet alone heard of any of the best films of 2024, as chosen by The Economist

Talkin' bout my generation (and others)

“The era when you were born has a substantial influence on your behaviors, attitudes, values, and personality traits. In fact, when you were born has a larger effect on your personality and attitudes than the family who raised you does.” - Jean M. Twenge, PhD

In interviews, Gagne has said that Wednesday Adams is a more helpful example of a sociopath, versus Patrick Bateman in “American Psycho.” Wednesday Adams has muted emotions and is indifferent to much of the world but still has a sense of right and wrong and a concern for her friends and family.

Interesting books. Knowing that some people are more prone to being criminals shouldn't change punitive outcomes, but studies looking into what preventative measures are effective could be useful.