📖 Zach Lambert talks about "Better Ways to Read the Bible"

I spoke to my friend and pastor about his new book, coming out August 12.

I’ve been blessed to call Zach Lambert my pastor and friend for almost two years now. Zach is the lead pastor at Restore Austin, which he helped found about a decade ago. On top of being a dad to two young sons, a husband, a prolific Substacker—all while pursuing of a Doctorate of Ministry at Duke University—he somehow found the time to write a new book, “Better Ways to Read the Bible.”

I was thrilled to get my hands on an early copy and read it within a matter of days. Zach has a deep knowledge and love of Scripture, even though he’s personally seen it used to cause harm. With the vast knowledge of a scholar and the skill of an experienced communicator, he walks readers through the harmful lenses that too many have encountered when reading the Bible. He then introduces more helpful lenses that Christians have used to deepen their faith in life-giving ways.

I recently got a chance to talk with Zach about his new book. That conversation is below.

Transcript lightly edited for clarity.

Ryan: Some might read the title, “Better ways to read the Bible,” and think that you're advocating for a radically new or even unorthodox way to read the Bible. But you're actually delving deep into Christian tradition to explain the helpful lenses. You also explain how some of the harmful lenses have been introduced more recently. Can you talk about that?

Zach: I think what I am trying to do is all under the umbrella of traditional orthodoxy when it comes to biblical interpretation. And it's really a reclamation of something in a lot of spaces, something very old. Augustine talked a lot about a Jesus-centered lens for biblical interpretation. I engage with him a little bit in the book. Obviously, that's a kind of traditional church father.

I think any time you are attempting to do something with a publisher that is connected to marketing, there's the risk of something coming across in a way that is sometimes not helpful. I had a conversation with someone about the subtitle, “Transforming a Weapon of Harm into a Tool of Healing.” And they were like, “So you're saying the Bible is a weapon of harm?” And I said, “Well, my desired subtitle was, “Transforming Something that Sometimes gets Turned into a Weapon of Healing,” but that was vetoed by the marketing department of the publisher. So a little bit of it was just like we're having some semantic conversations when it comes to titles and things like that.

But as you alluded to, once you dig into the actual book, it really is an attempt to reclaim some of the more beautiful ways of engaging with the text. One of the easier ones to point out, and how new it is, is the apocalypse lens. I talk a lot about what I call “Left Behind Theology,” and it's this relatively new invention in the grander scheme of Christian tradition. The kind of literalist interpretation of revelation that we assign modern meaning to is really not that old.

I tell this fascinating little story in the book about how it first originated. John Nelson Darby—according to quite a few people—essentially stole this entire biblical outlook from a teenage girl in rural Scotland who was prophesying in a tent meeting and said, “This is what revelation means.” I did enough research to know there's no way of knowing that for certain, but he was definitely at the tent meeting. She did share that. But that kind of stuff is really fascinating. That's only a couple hundred years old.

Even the version of inerrancy that we're familiar with was not codified until the 70s. There's always been this understanding of God's inspiration and God's involvement, how God inspires things through human authors. And that's been an ongoing, robust dialogue throughout 2,000 years of Christian history.

But the specific kind of inerrancy movement that was again codified in ‘78 with the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy is incredibly new. I'm not saying that like it's bad because it's new or it's good because it's old. I think that's a fallacy. But I am trying to say the Christian tradition is a lot bigger and more robust than we often give it credit for.

I often describe it like, if you come out of fundamentalist Christian spaces, it's like you were in a dark basement. And you were convinced by the other people in the basement that that's all there was, that that is what Christianity is, just that dark basement. And if you leave the basement, you are leaving Christianity. But what so many of us have discovered is that you walk up the stairs, open the basement door and you find this huge house with lots and lots of rooms. You see that the Christian tradition is so much bigger and more beautiful than we've understood for 2,000 years. And we've gotten things wrong. We've gotten things right, but we don't have to go and invent something new. We can actually reclaim something old.

Playing off that idea a little bit, can you talk about the tension between holding firm to core beliefs about the Bible while also letting go of the harmful beliefs or lenses? How do you discern between what's harmful and what's helpful?

Yeah, that is the question. I think we have to start with this understanding that we are all making those decisions all the time. We have to push back on this idea that some people just read the Bible black and white, and they're not doing interpretation. It just is what it is, because that's a lot of the tradition that I came out of. It's like, there's only one way, and it's this way that I'm presenting you.

I think most of us just intellectually and intuitively, if we've lived long enough and engaged with scripture, engaged in a broader tradition, we know that there are different ways of coming to different conclusions. The question is, what are the criteria that you're using to make those decisions? What I'm offering in the book is my attempt to say, after 15 years of pastoring, here are the handful of really harmful criteria that I've seen used to do biblical interpretation. And then here are some much more helpful criteria.

One of the healthy lenses I talke about is this lens of fruitfulness. And we talk about this in our church at Restore all the time: that Jesus said, “You'll know my followers by their fruit.” And that Fruit of the Spirit we know from Galatians is love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control.

We should be constantly asking, “Are my beliefs and my behaviors promoting love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, etc, in me and in the world around me?” And if the answer is no, that should at least cause us to pause and reevaluate some things to say, “Well, that's the work of the Spirit, and if the Spirit of Christ is not eliciting that fruit, then something is wrong.”

What I do in the book is say we should apply that to our Bible interpretation, too. Are these interpretations leading us to love, joy, peace, patience, etc.? And if they're not, it should at least cause us to reevaluate some things, because that is what Jesus said we should be known by as followers of Christ.

You're a very busy person. You have a lot of things going on. You're a father of two. You've helped found this church, you have a growing Substack, among many other things. Among these things, you are now a doctoral student at Duke. Is there anything that you've learned during your first semester or so at Duke about the Bible that's just blowing your mind, or just something really interesting that you’ve taken away from class?

That's such a good question.

I took an Old Testament class my first semester, and it was co-taught by Dr. Ellen Davis, who is a Christian Old Testament scholar, one of the preeminent in the world. She's in her 80s and is just this powerhouse of a woman who is still teaching. It's one of those that is such an honor to just sit in her class, because she's such a legend.

There were a couple of times that she co-taught with a rabbi, Shai Held. I remember there was this incredible light bulb moment where we were talking about the inspiration of Scripture. We discussed how we engage with Scripture, just intellectually, trying to wrap our minds around it, and then try to communicate it to people that we're leading.

Side note: I think our mutual friend Karen Keen and “The Word of a Humble God” does that as good as anybody. That's probably my favorite book on the subject.

Yeah, I’ve got that book right over there on my bookshelf.

So we're having this conversation. And they were asking the Christian students, “How were you taught to recognize the inspiration of Scripture?” And pretty universally, we were taught: We know the Bible is inspired by God because we can dive into a text and discern one truth. There is one proper and godly interpretation. And because God is not a God of chaos, and you know all those things, there is one truth in every text.

The rabbi was stunned. He was like, That is the exact opposite of how we talk about inspiration. We talk about inspiration as we know God's involved, because there are so many beautiful truths that can come from any given text as we engage with it. It's like a crystal that we turn, and the light reflects, refracts in different ways and shows us different beautiful things. And that's not to say that there aren’t bad interpretations or better interpretations.

That's the entire point of the book. It was this light bulb moment of: God is a lot bigger than us. That was a really cool moment that I've talked about a bunch since then, because I think it's the kind of midrashic tradition in the Hebrew Scriptures that we get from Jewish folks. It's actually, I think, really helpful.

I'm sure you're learning so much more than you can probably take in.

As a pastor, obviously, Scripture and the Bible are very important to you. Jesus, of course, is central. As you've been on your own journey, how would you say that’s all remained a key part of your life: not just Jesus, not just the Bible, but Christianity?

Yeah. Great question. You know, my friend Trey Ferguson, who's a pastor and author as well, talks about how there's really not “Christianity” singular. There are Christianities. There have been versions of our faith for 2000 years, and obviously existing today. And I think that we get in a lot of trouble when we dismiss this kind of broad Christianity as outdated or completely harmful.

I think there's a popular movement in some more progressive spaces that I am in and out of where it's like, well, Christianity is just like this white man's religion. Christianity is inherently white supremacist and things like that. And we have to be honest and say Christianity has been used in the service of white supremacy, the Klan, and we see it today with you know, Christian nationalism and Christo-fascism stuff.

But it was started by a dark-skinned Jewish man in Palestine. And so the idea that it's inherently white supremacist is ridiculous. And I think even the idea that Christianity is inherently harmful is ridiculous. I think we can be and should be honest about the ways it's been used in a harmful thing. But I think we also have a responsibility to be honest about the good that it's done in the world.

I'm a huge student of the 1950s and 60s and the Civil Rights Movement that was led almost exclusively by Christians and Christian clergy. The movement was led by mostly black Christian clergy, but also white and Latino/Latina Christian clergy, and so many others, like the Freedom Riders. It was a rainbow coalition, as King talked about, and it was people who were mostly motivated by faith. That was the reason that they did the things that they did. And so that is every bit as much of our tradition as, you know, the Christianity of the Klan, or something like that.

I think we get to choose what kind of Christianity we inhabit. We get to choose how we follow Jesus. And how we interpret the Bible is connected to all that. And I think we can lean into the legacy of people who have both experienced and expressed Christianity in these beautiful, Jesus-centric ways.

You've heard me say this a million times: we should not throw all of it away. We should be reclaiming and stepping into the good and beautiful parts while simultaneously condemning other things. I'm actually a lot more interested in stepping into the good and the beautiful, which provides a natural critique of the harmful.

I think we do direct critiques, too, obviously. But I think if all you do is critique the bad and the old and all that, then you actually don't ever have time for imagination, for something new and beautiful or old and beautiful. And I'm just so much more interested in that, and I think it's such a more compelling message than just, like, constant condemnation.

That's been something on my mind, too. Deconstruction can be a healthy part of your faith walk and faith journey and there are things you have to let go of and maybe explore new ideas and new ways. But also when it becomes just deconstructing all the way into nothingness, that’s not a helpful thing.

All right, so wrapping up but also zooming out a little bit . When you think about the American church, what is something that keeps you up at night?

Yeah. I mean, there are so many things, but I think currently top of mind for me is the use of Christianity to give divine credence to cruelty.

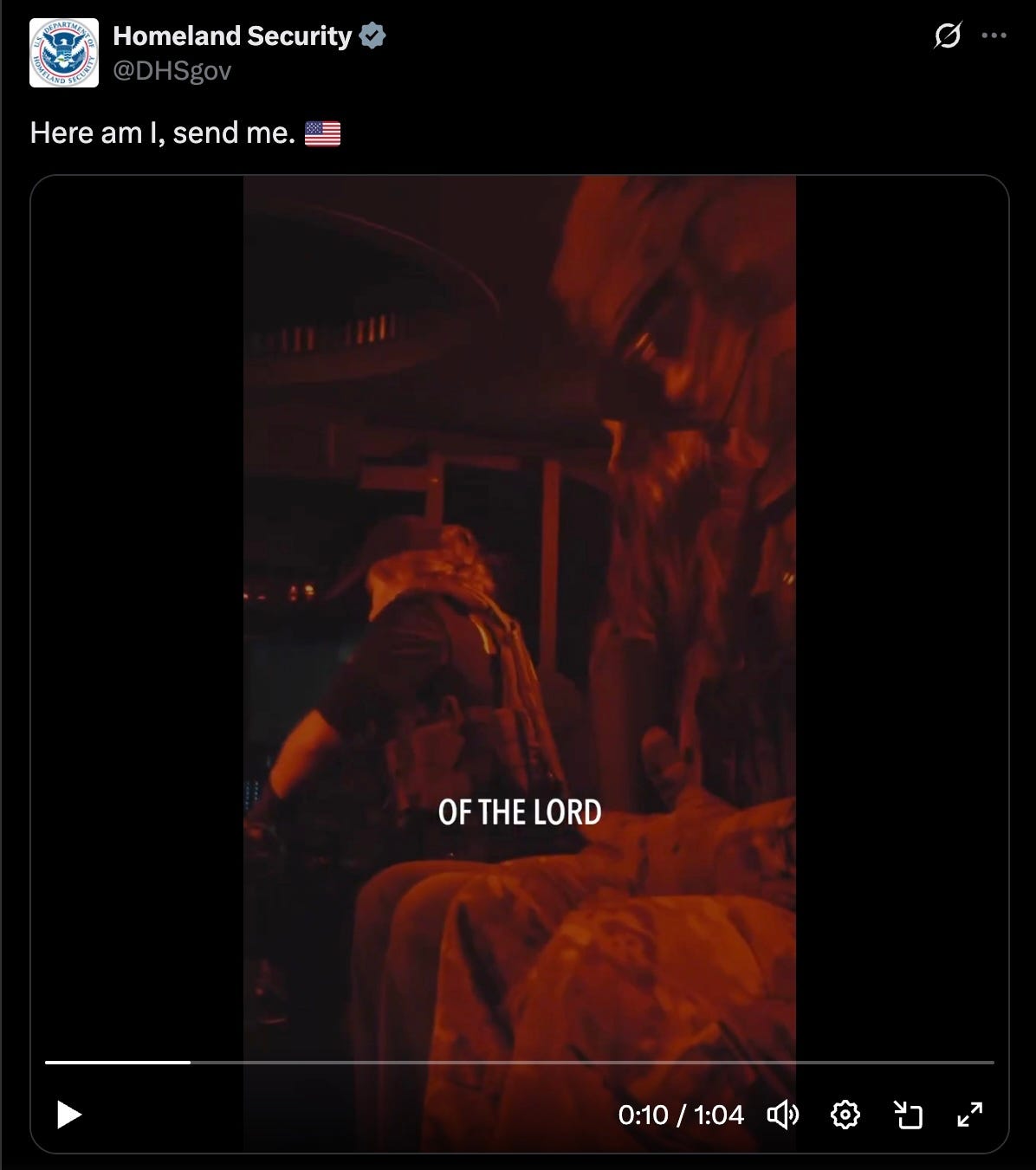

I posted about a week or so ago that the Department of Homeland Security had run this video quoting Isaiah, “Here am I, send me,” with b-roll of ICE agents and that stuff.

I mean, it's not subtle. We have myriad videos of out-of-uniform ICE agents grabbing people off the street. We know what the detention centers are like, and “Alligator Alcatraz” and the flights to El Salvador, just horrific things. And that video is very explicitly saying, “God has ordained this. God has sent this,” and, Oh, that makes me emotional.

I think it's hard to understate just how truly damaging that is. The most important thing is to love God and love your neighbor as yourself. And when he got asked about who the neighbor was, he basically described the person that you have the least in common with, the person that you have the most historical struggles with—that's the person that you're supposed to go to and support and help.

And yet, the words of that God are now being used to justify violence and really horrible things. And so that's a microcosm, but it's happening. It's happening really broadly in our country, and a lot of people are eating it up, you know? If you can give divine justification to people's worst impulses, and they don't have to deal with shame or guilt or anything like that, it's the ultimate trump card: Maybe this doesn't seem right to you, but God said to do it. God sent me to do it. There's no more powerful trump card motivation than that, right? So, yeah, that is killing me for sure.

It's pretty dark stuff. So then on the flip side: when you think about the church and where things are headed, what is something that gives you hope about the future?

I think that I'm seeing more and more people not settling for a deconstruction-only version of Christianity. People are realizing that a deconstruction-only ethic really just leads to a place of demolition of faith and even institutions that are massively imperfect but are pillars of democracy and really help people.

I get on a rant about this whole “tax the churches” movement. And, listen, I get it. I get that somebody sees a megachurch pastor making millions and millions of dollars and a private jet. It's easy to be like, it's crazy that they don't pay taxes.

Well, the pastor does pay taxes, first of all. Second of all, I get why you would want to tax that church. But .0001% of churches are like that. So many churches are in communities, especially rural communities, where they are the community center. That’s where people vote. That’s where they do weddings and funerals. I mean, they are the hub of everything. And if you start going after them or taxing them, they will no longer be able to afford the property that they have, they'll go under, and a lot of these towns will be left without places for people to gather and do community and all of that stuff.

We just had these horrible floods right in Central Texas and Kerrville, and we found two churches on the ground who were doing amazing direct care, and we made donations directly to those churches there on the ground. Now they're churches that we would probably have theological or ideological disagreements with, but they are on the ground literally saving people's lives, providing shelter, immediate assistance, all of that kind of stuff. Without them, things would have been so much worse.

That gives me hope that people are not settling for a deconstruction-only ethic when it comes to Christianity, that they are interested in building something new, in building broader coalitions. They are interested in standing in the gap for people and locking arms with people, even without full agreement on every single thing to do common good.

As Frederick Douglas said, “I’ll unite with anybody to do right and with nobody to do wrong.” I really appreciate that as an ideal of we can't be bound by every single thing that divides us. We can come together to do good things. And on the flip side, even if we've got all the ideological agreement in the world, if somebody's doing something harmful, we should not be partnering with them.

I love that. That's a beautiful sentiment of just a church meeting a need, and that can transcend ideological and various disagreements. At the end of the day, it's about being the hands and feet of Jesus.

“Better Ways to Read the Bible” releases August 12.

🏳️🌈With allies like these, who needs adversaries?

Abandoning Christianity, drag shows in church, appearing to cheer political violence, dismissing dissent and other ways to set the cause of same-sex marriage backwards, not forwards. A version of this post now appears in Baptist News Global.

Divorce, double standards and debates on same-sex marriage

The topic of divorce is messy and complex, impacting real people with real lives. Same-sex marriage is academic. A version of this post is now featured on Baptist News Global.

I got another phone call from the fraternity president

I was at lunch with family when a phone call came in, followed by a text message. It was “Brad,” the former fraternity president now pastor I had mentioned in my two-part series on pled…

I’m reading Better Ways to Read the Bible right now. Loved seeing this Post from you:)

Loved chatting with you, my friend!