Lorne Michaels thought SNL writers "lost their minds" in 2016.

Tina Fey and Mike Myers built characters around him. Conan felt abandoned by him. And other highlights from the authorized biography, "Lorne: The man who invented Saturday Night Live."

To me, one of the most, if not the most, interesting aspects is the relationship of Lorne to the cast. And all of the permutations that Lorne, as father figure, or as authority figure, goes through. — Candice Bergen, Host

I have gained an enormous respect for Lorne Michaels and his ability to see beyond his ego. He never said anything but great things about me—even though he fired me. I remember there was a kid on the show who had a drug problem, and Lorne would put him in rehab and take care of him and pay him while he was there and then bring him back on the show. — Damon Wayans, Cast Member

My secret assumption about Lorne is that he may suffer from such a deep case of self-loathing that if you agree to be on his show and you are nice to him, he cannot respect you. So therefore you are left to wallow in your own despair. — Janeane Garofalo, Cast Member

I talk to Lorne regularly about everything… I have to make appointments to see him, because I’ll talk to him for an hour if I can… Whatever it is, he’ll give me advice on it. He’s just really great. — Jimmy Fallon, Cast Member

I swear to God—and I’ve been around this guy for almost 30 years—Lorne has no interest in what you want to talk about. None. What Lorne thinks is, if you need him to help you solve it, it’s not worth solving.” — James Signorelli, Director of Commercial Parodies

Lorne’s a good friend. — Rudy Giuliani (circa 2011)

[The above quotes were taken from "Live from New York: The Complete, Uncensored History of Saturday Night Live as Told by Its Stars, Writers, and Guests."]

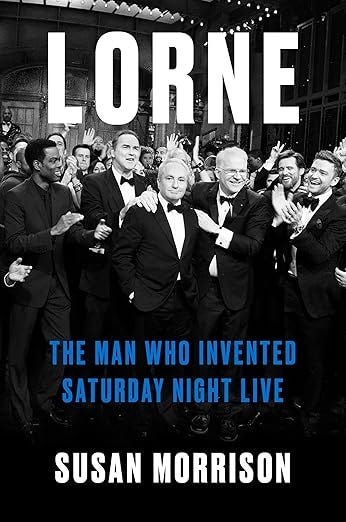

As the executive producer of “Saturday Night Live” for 45 of its 50 years, Lorne Michaels has launched the careers of dozens of movie stars and two hosts of “The Tonight Show;” produced more than 20 movies including “Wayne’s World,” “Three Amigos” and “Mean Girls,” which later became a hit broadway musical, also produced by Lorne; produced more than 50 TV shows, including “30 Rock,” “Portlandia,” “Late Night with Seth Meyers,” and of course, nearly 900 episodes of “Saturday Night Live.”

His cultural impact is undeniable.

Tina Fey based the worldly persona of fictional NBC executive Jack Donaghy on Lorne. Alec Baldwin joked that Lorne keeps a tuxedo in his glove compartment and drew inspiration from his not-so-subtle elitism.

Less flattering, Mike Myers’ based his Dr. Evil character in the Austin Powers franchise on Michael’s speaking style and demeanor. The iconic pinky to the mouth was actually an invention of Dana Carvey, who meant it as a private joke while backstage at SNL. He was shocked to see his entire impression appropriated for a movie.

Lorne has been mimicked in multiple episodes of “The Simpsons.” He was the inspiration for a movie character in “Brain Candy,” produced by The Kids in the Hall. He is as much an iconic “character” on SNL as Church Lady or Mary Katherine Gallagher.

But who is Lorne Michaels, really?

A Canadian childhood marked by tragedy

Lorne Michaels was born Lorne David Lipowitz in Toronto, Canada, eight decades ago. His father died suddenly when Lorne was a young teenager and some have speculated that this jarring life event is why Lorne always needs to know what is happening around him. His need for control may be the product of a young life marked by sudden tragedy.

His mother was cold and emotionally distant. SNL cast members will often complain that Lorne is cold and aloof, but perhaps this is just how he was raised. Others who have grown close to Lorne, describe him as warm.

The emotional distance Lorne keeps between him and his underlings may also be out of necessity. In reading various histories of SNL, it’s clear the first five years were marked by few, if any, boundaries. Gilda Radner would call Lorne almost every night to talk about her personal issues. The combustible John Belushi stayed with Lorne for several weeks, almost burning Lorne’s house down after a mattress caught fire.

Lorne would become a father figure (now a grandfather figure) to many cast members but in the early days he was more of a peer. And it was a mess.

The wilderness years

After five years, Lorne quit SNL. He was burned out from producing a show while trying to manage the growing egos of the young cast members.

Lorne had launched SNL when he was 30, a stunning level of success for someone so young. That kind of success proved elusive during the next few years. He produced a standup movie with Gilda Radner, but it flopped. He had a development deal with MGM, but multiple projects never saw the light of day. He finally produced a film starring Dan Akroyd and Bill Murray, but it became an arthouse film that was so underwhelming MGM decided not to release it.

A few years into his wandering, NBC lured him back to produce a variety show, The New Show. It would be similar to SNL, but taped and on Friday nights. It was a disaster. Even those who worked on the show didn’t seem to know what it was meant to be.

The experience revealed just how much Lorne needed the pressure of a live show to keep him focused. He would ask to redo scenes multiple times, exasperating the live audience. He would edit and re-edit and second-guess his choices until time ran out. All this extra producing and editing did not make the show better. In many cases, the end result was worse.

“The New Show” was the lowest-rated out of 94 shows that season and ended after nine episodes.

At the end of five years, when Dick Ebersol decided he would leave as executive producer of SNL, Lorne was more eager to retake the reins. He has stayed on ever since returning in 1985.

While many were on Team Coco, Lorne was on the sidelines

Lorne began to expand his late-night empire in the early 90s when he was chosen to develop and then produce “Late Night” after David Letterman famously left NBC. The network executives were looking for a big name. Lorne suggested an unknown comedy writer who had rarely appeared on television: Conan O’Brien.

It was an enormous gamble. But it paid off. Conan would host Late Night for 16 years until it became time for him to take over The Tonight Show—as outlined in his contract.

When Conan took over The Tonight Show, Lorne was not named as executive producer. Conan had assumed Lorne would not be producing as the show was in Burbank, California, and Lorne would remain in NYC, obviously. But NBC—who wanted to avoid paying Lorne a hefty salary for a largely ceremonial role—began to float a narrative that Conan didn’t want Lorne involved.

When Conan was blindsided by the news that “The Tonight Show” would be bumped to 12:05 a.m., after Jay Leno retook the regular 11:35 p.m. slot, he was stung to learn Lorne knew of the news before he did.

Lorne disagreed with Conan’s instinct to put out a letter addressed to “People of Earth” that laid out his decision against hosting a show at 12:05 a.m. He would have counseled him differently, had Conan asked for his advice. Conan might have asked for his advice, if he hadn’t felt abandoned by Lorne:

Lorne could have said, “You know what? They didn’t really give Conan a chance. Conan’s proven he can do this.” He could’ve said some positive things about me, and he wouldn’t have lost anything. He’s Lorne f—ing Michaels. That’s what bothered me.

When SNL celebrated its 40th anniversary five years later, Conan wasn’t there. He was filming his new show in Cuba. Conan was off the coveted Christmas gift list.

Now, Conan sees things differently:

I understand now that NBC had been Lorne’s bread and butter since 1975—I was an ancillary thing. In retrospect, I get why he was torn and wanted to lay low. I’ve made my peace with it. We’re friends, and I love the guy.

Lorne thought the writers “lost their minds” during the Trump era. Some former cast members did, too.

The cold open after Donald Trump won the 2016 Presidential Election featured Kate McKinnon as Hillary Clinton playing Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah” on the piano. Unlike the first cold open after 9/11, there were no jokes. There was no laughter. Just a moment that was as sanctimonious as it was devoid of humor.

When Chris Rock had watched the rehearsal backstage earlier in the week, he turned to Lorne and said, “Where are the jokes?”

He wasn’t the only SNL alum who was baffled:

“What was that?” many asked each other. “I thought, ‘Was Lorne absent this week?’” one alum recalled. To old-timers, the mawkish righteousness of the bit palled. Michaels didn’t much like it either (“I can’t do emotion and I can’t do bias,” he recalled thinking), but he preferred “Hallelujah” to the alternative.

As ridiculous as that cold open was, it was almost much, much worse. The writers had pushed hard for McKinnon to sit at the piano and sing John Lennon’s “Imagine,” as female cast members shared glum testimonials about what Hillary Clinton’s candidacy meant to them. Lorne negotiated them down to Cohen’s “Hallelujah” with no self-pitying testimonials.

He later told an SNL veteran, “The writers have lost their minds.”

Lorne was constantly battling the writers over how partisan to make the show. And it became a losing battle:

“It’s the hardest thing for me to explain to this generation that the show is nonpartisan,” Michaels said, two weeks before the election. “We have our biases, we have our people we like better than others, but you can’t be Samantha Bee.” He meant one-sided and strident.

As the cold opens with Alec Baldwin became “basically beat-for-beat transcripts of idiotic things Trump had said the previous week,” SNL alums felt the show was sacrificing comedy for the sake of self-righteousness:

[Former longtime SNL writer] Jim Downey was no Trump supporter, but, watching from home, he sometimes felt that the show’s political material seemed like a product of “the comedy division of the DNC,” something that Michaels generally took pains to avoid… Will Ferrell found the quantity of Trump material “almost oppressive.”

The “Trump Season” of SNL would later earn 22 Emmy nominations.

November 3, 2018

In her research for the book, Susan Morrison spent a full week shadowing Lorne to see what his role is really like at SNL.

The week leading up to the November 3, 2018, show was typical—in that it was pure chaos. Pete Davidson had recently broken up with Ariana Grande, who that week sent her infamous “thank u, next” tweet in response to Davidson’s joke in the SNL promo. The host, Jonah Hill, was being a bit of a diva about his vision for a sketch that wasn’t landing with anyone else. Alec Baldwin, practically a regular cast member thanks to his Trump impression, had been arrested for punching a man over a parking space.

The usual.

The egos of the cast members needed to be managed along with the unique demands of the show. A sketch involving pugs required a call to the show’s regular animal provider (there is a llama always on standby). An actual van is needed for one of the sketches, but the van will need to be cut in two to fit into the elevators at 30 Rockefeller Plaza. Jonah Hill is being inducted into the five-timers club, so which celebrities will be in town to help with the cold open?

Throughout the week, Lorne keeps a somewhat hands-off approach to the show, taking input from writers and cast members while letting their ideas develop. That all changes at dress rehearsal. In the 90 minutes between dress rehearsal and the live show, Lorne is ruthless:

He is definite and direct in a way that he is not during the rest of the week, a mode he describes as “being on knifepoint.” His aversion to confrontation is outweighed by the urgent need for triage. He issues orders quickly. There is less of the usual joshing around, and when it occurs, Michaels can lash out.

The Steven Seagal character is cut from a Fox News sketch. The Craigslist Van sketch that required a van hauled up to the studio is cut. A gasp is needed at the beginning of a Kate McKinnon sketch. A higher chair is needed for Jonah Hill’s Benihana sketch. Hill’s favorite sketch about a pretentious movie theater concession stand is cut.

Edits are made to the cue cards. Costumes are adjusted. Cast members are informed of changes. The pugs are prepared. Lorne settles into his seat below the bleachers as the countdown begins—just as he has for the 853 episodes before.

A favorite saying of Lorne’s is: “The show doesn’t go on because it’s ready, it goes on because it’s 11:35 p.m.”

John Belushi, Jane Curtin, Bill Murray and Will Ferrell all hated Chevy Chase. Everyone did.

“I don’t think it will ever work because the audience for which it’s designed will never come home on Saturday night to watch it.”

Why did SNL pull its punches on Biden?

One of Michaels’ rules was, no groveling to the audience either in the studio or at home. In those first five years especially, SNL writers were not pleased when a studio audience applauded some social sentiment or political opinion in a sketch or “Weekend Update” item. The writers wanted laughs, not consensus.